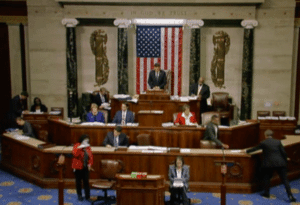

Let me begin by saying god bless Congressman Patrick McHenry. He is out there on the front lines actually trying to make a difference and help entrepreneurs and small businesses get off the ground and succeed. Of course, no good deed goes unpunished, and a punishing is what his proposed Fix Crowdfunding Bill received in order to get passed by the House last July. Granted it was a landslide victory, because NEWSFLASH! – this is a bipartisan issue, and anyone who tells you different does not understand the economy, politics or both. The rub is, in addition to being stripped of many of the most valuable features, the bill also acquired a lot of regulatory detritus that threatens to make this “solution” more of a problem.

What could have been…

The wonderful provisions that were ultimately stricken from the original bill would have achieved some practical and vital results such as (listed in my order of preference):

The wonderful provisions that were ultimately stricken from the original bill would have achieved some practical and vital results such as (listed in my order of preference):

1. Allow for Regulation Crowdfunding deals to engage in “testing the waters” or the ability to solicit interest in your deal before actually filing the documents with the SEC and going through the expense of launching an offering. This feature is invaluable for cash-strapped companies who could use this to determine if they should even go through the time and expense of conducting a securities offering or instead head back to the drawing board to refine their product or business plan.

2. Raise the maximum offering amount to $5 million in a rolling 12-month period from $1 million. While I don’t believe this is necessary for these early days for entrepreneurs and small business, I do think this would go a long way in eliminating the quality bias or “race to the bottom” of companies that use Regulation Crowdfunding as a last resort, by attracting more established companies with higher capital requirements to utilize the regulations.

3. Clarify that a funding portal does NOT bear issuer level liability unless it knowingly participates in the fraud.

4.  Simplify and potentially increase the amount that individuals can invest in crowdfunding. Currently, the rule is an overly complex capping the amount an investor can invest in all Regulation Crowdfunding deals in a 12-month period at an amount based on a percentage of the lesser of your income or net worth. This disadvantages people (generally the young and the old) who either generate income but haven’t yet acquired the assets to attain significant net worth or those who no longer generate significant income but have sufficient assets due to a lifetime of earning income. Although it left the complexity, the original bill allowed for the investment amount to be based on the greater of income or net worth accommodating individuals who are on both ends of the spectrum.

Simplify and potentially increase the amount that individuals can invest in crowdfunding. Currently, the rule is an overly complex capping the amount an investor can invest in all Regulation Crowdfunding deals in a 12-month period at an amount based on a percentage of the lesser of your income or net worth. This disadvantages people (generally the young and the old) who either generate income but haven’t yet acquired the assets to attain significant net worth or those who no longer generate significant income but have sufficient assets due to a lifetime of earning income. Although it left the complexity, the original bill allowed for the investment amount to be based on the greater of income or net worth accommodating individuals who are on both ends of the spectrum.

5. Clarify what a funding portal MUST do with respect to preventing fraud and screening candidates on its platform – which boils down to conducting backgrounds checks on issuers, officers, and 20% owners and to the extent the funding portal knows or learns of any prior fraud or attempted fraud to decline to list the issuer on its site.

6. Create a grace period, whereby a funding portal could not be found in violation of the Regulation Crowdfunding until 2021. This was a pipe dream and I had no illusion of it passing.

So with all of that laid to waste, what did make it? And in what form?

The only two provisions that survived, though significantly altered were a provision allowing for the use of special purpose vehicles to collect the crowdfunding investors in so they do not overly complicate the cap table of the company raising money and the revision to the Rule 12(g) caps. This is what we have to work with, and it will take some work…

The only two provisions that survived, though significantly altered were a provision allowing for the use of special purpose vehicles to collect the crowdfunding investors in so they do not overly complicate the cap table of the company raising money and the revision to the Rule 12(g) caps. This is what we have to work with, and it will take some work…

The original bill allowed for the use of special purpose vehicles (“SPVs”) in a crowdfunding scenario by amending both Title III and the Investment Company Act. This is a fairly complicated area of law but the basic issue is that SPVs which allow for the aggregation of investor funds to invest in other companies usually fall under the Investment Company Act of 1940 or are subject to an exemption based on certain characteristics. Title III prohibited the use of investment companies or companies taking an advantage of an exemption from being an investment company from using Regulation Crowdfunding. The original bill attempted to remedy this by specifically carving out the use of SPVs, which would only hold the securities of one issuer that was also utilizing Regulation Crowdfunding, and allowing them to take advantage of the new rule. This would be extremely beneficial to crowdfunding issuers who are concerned with managing an unwieldy cap table and the chilling effect it could have on future rounds of financing because the company would simply have one investor, the SPV, rather than potentially thousands of crowdfunding investors.

The way this structure is implemented in the accredited investing world is that the SPV is set up by the online platform (or an affiliate) and the platform (or an affiliate) receives a fee for managing the SPV. Usually some variation of 2% of the value of the securities sold and 20% of any appreciation in those securities. This aligns the manager and the investor because the meaningful chunk of the compensation only occurs if the company is successful in the long term. The services that are provided are the management of the SPV, making any distributions to investors, making sure the K-1s or other tax documents are distributed to investors, making sure any mandated information is distributed to investors, keeping track of investors and any transfers of interests.

One thing both the original bill and the one that ultimately passed would not allow for is the creation of funds where the crowd could invest in a basket of crowdfunded companies (say all companies that raised funds successfully on a particular funding portal in a year) and thus diversify their investments. These vehicles have been successful in the UK on platforms such as CrowdCube and Seedrs and for accredited crowdfunding investors in the US with such funds as AngelList and Funder’sClub showing 46% and 37.1% IRR, respectively. The requirement that the SPV hold the securities of a single issuer prevents this.

One thing both the original bill and the one that ultimately passed would not allow for is the creation of funds where the crowd could invest in a basket of crowdfunded companies (say all companies that raised funds successfully on a particular funding portal in a year) and thus diversify their investments. These vehicles have been successful in the UK on platforms such as CrowdCube and Seedrs and for accredited crowdfunding investors in the US with such funds as AngelList and Funder’sClub showing 46% and 37.1% IRR, respectively. The requirement that the SPV hold the securities of a single issuer prevents this.

But I digress—one problem at a time! So the version of the Fix Crowdfunding Act that ultimately passed in the House contains additional language requiring that in order to receive compensation for or from such SPV, the person or entity receiving such compensation must be acting as, or on behalf of, an either federally or state registered investment advisor. This adds an entirely new level of regulation and frankly doesn’t make much sense. In order to be an “investment advisor” pursuant to the federal and most state regulations, an entity must meet the following three criteria:

- receives compensation;

- for engaging in the business of;

- providing advice to others or issuing reports or analyses regarding securities.

As you can see from the activities and services that are provided to the SPV above in the accredited investment context (and we have every reason to believe that this model will be applied in the retail Title III context) providing investment advice or reports and analysis regarding securities are not in the wheelhouse of managers of these type of SPVs.

Why do we now need to go hire an additional service provider to simply increase costs for both investors and companies?

The managers of the SPVs do not provide investment advice, in fact in most cases the SPV isn’t even formed until the investment decision has been made, the target amount has been reached and the funds are released from escrow. Additionally, the managers do not provide investment advice on an ongoing basis as the securities operate by their terms and the manager has no discretion over whether they are bought or sold. Furthermore, the manager does not provide reports or analysis, but rather acts as a conduit between issuer and investor providing the mandated disclosure either by the terms of the securities or by law. The manager simply operates the SPV and conducts the mechanics to service the investors therein. There is no judgment or discretion being applied. This is a job most suited for the funding portal or an affiliate thereof. And guess what? Funding portals are already regulated by the SEC and FINRA!

Now we can rest assured that these SPVs will not run amok in a lawless environment. The revisers of the original bill probably envisioned the funding portals or their affiliates registering as investment advisors in order to conduct this business, but it is not clear they would even qualify based on the services they provide and more importantly, why should they do so if they are already regulated as funding portals by the SEC and FINRA as funding portals?

Of course, the managers should be able to receive compensation for their valuable services, but requiring them to be investment advisors to do so will only add additional burdens and costs to the very constituents the JOBS Act was intended to help. Plus, as I mentioned it is apples and oranges – in the scenario laid out, there are no advisory services to perform which makes the requirement completely inapplicable.

The other provision to survive was a revision to the 12(g) cap exemption that is in Regulation Crowdfunding. Section 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act requires that companies that have over 500 unaccredited holders or 2,000 accredited holders and $10 million in assets have to file as public reporting companies with the SEC.

In the current Regulation Crowdfunding, there is an exemption for companies that are over the holder limits due to crowdfunding investors, have less than $25 million in assets and have engaged a third party transfer agent. This is a plus, but pretty complicated and adds additional expense of a transfer agent and the threat that if you are successful and achieve a certain amount of assets you will be punished with public reporting.

Elegance in Simplicity

In McHenry’s original bill he simply and elegantly provided for an exemption from the 12(g) reporting requirements for all companies whose crowdfunding investors push them over the limits, period. Simple, understandable and administrable—my favorite kind of law. Unfortunately, this got revised to first allow for an exemption for companies that have a public float of less that $75 million which is a public company concept and inapplicable to crowdfunding. As you know, public companies are ineligible to use Regulation Crowdfunding. I frankly do not know what this language is doing here.

In McHenry’s original bill he simply and elegantly provided for an exemption from the 12(g) reporting requirements for all companies whose crowdfunding investors push them over the limits, period. Simple, understandable and administrable—my favorite kind of law. Unfortunately, this got revised to first allow for an exemption for companies that have a public float of less that $75 million which is a public company concept and inapplicable to crowdfunding. As you know, public companies are ineligible to use Regulation Crowdfunding. I frankly do not know what this language is doing here.

Secondly, the revised bill allows an exemption for crowdfunded companies that have less than $50 million in revenue and no reference to a third party transfer agent. While I guess it is good to not have the added expense of a transfer agent (although with a significant number of beneficial holders it may be helpful), I do not know if the $50 million revenue cap is better or worse than the $25 million asset cap we currently have. It would seem to just benefit certain types of companies over others. For capital intensive companies such as manufacturing or biotech you would prefer a revenue test, tech and services companies would prefer an asset test.

So there you have it—what Congressman McHenry’s bill has been reduced to…

While I am the first to appreciate anything that will make capital raising for small business more efficient, we need to fix this fix in order for this piece of legislation to do so.

Georgia P. Quinn is a Senior Contributor for Crowdfund Insider. She is also the CEO and co-founder of iDisclose, an adaptive web-based application that enables entrepreneurs to prepare customized institutional grade private placement documents for a fraction of the time and cost. Georgia also serves as of counsel at a leading law firm in crowdfunding, Ellenoff, Grossman & Schole, specializing in facilitating financial transactions and compliance with JOBS Act regulations.

Georgia P. Quinn is a Senior Contributor for Crowdfund Insider. She is also the CEO and co-founder of iDisclose, an adaptive web-based application that enables entrepreneurs to prepare customized institutional grade private placement documents for a fraction of the time and cost. Georgia also serves as of counsel at a leading law firm in crowdfunding, Ellenoff, Grossman & Schole, specializing in facilitating financial transactions and compliance with JOBS Act regulations.