With the recent confirmation of Mary Jo White as Chairman of the SEC and Kara Stein, and Michael Piwowar as SEC Commissioners, the leadership of the SEC is undergoing significant changes that will affect public policy for years to come. It has been argued that White’s nomination and confirmation by unanimous consent can been seen as a statement by the Administration and the Senate that they want a “cop on the beat” to help police the alleged excesses of Wall Street. While this is an important message for the SEC to send, when the next vacancy comes up the President and Senate should consider sending another important message: “Small businesses and startups matter, too.”

With the recent confirmation of Mary Jo White as Chairman of the SEC and Kara Stein, and Michael Piwowar as SEC Commissioners, the leadership of the SEC is undergoing significant changes that will affect public policy for years to come. It has been argued that White’s nomination and confirmation by unanimous consent can been seen as a statement by the Administration and the Senate that they want a “cop on the beat” to help police the alleged excesses of Wall Street. While this is an important message for the SEC to send, when the next vacancy comes up the President and Senate should consider sending another important message: “Small businesses and startups matter, too.”

It seems obvious that the SEC should care about small businesses and start-ups since those companies provide most of the job growth and innovation in this country, but the SEC’s traditional focus has never been on small businesses. For the vast majority of its history, the SEC has primarily focused on the public markets, where by necessity companies tended to be larger. In fact, until recently very small companies were not allowed to sell securities to the general public without going through an onerous registration process.

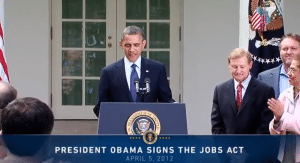

That began to change last year with the passage of the JOBS Act. Realizing that small businesses and startups needed better access to capital, Congress and President Obama modified long-standing securities law to allow small companies to sell securities to the general public via investment platforms without having to undertake the expensive and burdensome process of registering with the SEC. This shift, and others in the JOBS Act, will provide broader access to the capital markets -and the SEC oversight that comes with it- to companies smaller and less established than in the past.

That began to change last year with the passage of the JOBS Act. Realizing that small businesses and startups needed better access to capital, Congress and President Obama modified long-standing securities law to allow small companies to sell securities to the general public via investment platforms without having to undertake the expensive and burdensome process of registering with the SEC. This shift, and others in the JOBS Act, will provide broader access to the capital markets -and the SEC oversight that comes with it- to companies smaller and less established than in the past.

The SEC, with its mandate to both protect investors from fraud and, importantly, facilitate capital formation, will see its scope now expanded to cover every mom-and-pop bakery or “three people in a garage” startup that wants to pursue investment. It will have to focus on how to create and maintain a regulatory and enforcement framework that prevents fraud without being so onerous or cumbersome as to stifle innovation and access to capital by these small businesses.

To do this the SEC needs expertise in how these small, young companies operate and the pressures and limitations they face. While small businesses and early-stage startups are a diverse lot, they tend to have common differences from the larger companies the SEC traditionally focused on — differences that are important in dealing with regulation. In particular, while small companies often rely on being able to make decisions more quickly than their larger competitors, they generally lack the money and staffing enjoyed by larger firms, which makes it harder for them wait until the regulations are settled before beginning to take action. Likewise, they are less able to afford lawyers steeped in the metaphysics of securities law to analyze regulations, making transparency in both process and result essential to fair regulation. If the SEC is perceived as indifferent to the needs of small businesses, or worse is seen as favoring big business substantively and procedurally, it will damage both the Commission itself and Americans’ faith in a free and fair market.

Additionally, the SEC now has to worry about protecting investors from frauds masquerading as small businesses. Fraudulent small business will pose a different type of challenge than traditional securities fraud. They will not be able to bury financial deception in a massive company like Enron and MCI Worldcom. Instead this new class of fraudsters will be able to hide among the millions of legitimate small companies seeking investment. Being able to find the few bad apples in the giant apple orchard of American small business, without unduly burdening the honest ones, will be essential, and requires a keen understanding of how small and young companies operate.

Additionally, the SEC now has to worry about protecting investors from frauds masquerading as small businesses. Fraudulent small business will pose a different type of challenge than traditional securities fraud. They will not be able to bury financial deception in a massive company like Enron and MCI Worldcom. Instead this new class of fraudsters will be able to hide among the millions of legitimate small companies seeking investment. Being able to find the few bad apples in the giant apple orchard of American small business, without unduly burdening the honest ones, will be essential, and requires a keen understanding of how small and young companies operate.

This expertise is not necessarily developed working for a Wall Street law firm or bank, or on the congressional committees that generally serve as feeders for the Commission. This is not to imply that the current commissioners are unable or unwilling to appreciate the unique nature of small businesses, but the knowledge base that made them attractive commissioners is their depth of understanding of the SEC’s traditional focus: large companies and the established public markets.

Fortunately, there are numerous high quality candidates outside of the axis of Wall Street, Banking-Financial Services committee, and traditional securities law. Law firms with a more entrepreneurial focus, the congressional committees that deal with small business issues, and academic programs focusing on the economics and law of entrepreneurship all provide rich sources for intelligent, capable professionals who can provide the benefit of their experience to their fellow commissioners on the unique nature and needs of American small business. The President and Senate should step out of their traditional comfort zones and be actively looking to these areas for a new Commissioner who can help give modernize the SEC’s knowledge base.

The SEC now has a mandate to help and protect small businesses and investors. Hopefully they will, when the next opportunity arises, fully embrace this new sector with an appropriately experienced voice on the Commission.

Brian R. Knight, Co-Founder and Vice President for Platform Services at CrowdCheck, has experience as both an attorney and an entrepreneur. Brian has served as an attorney in the private sector and for the Federal Government. He also started and ran Publius Incorporated, a business focused on improving constituent communications with elected officials. Brian brings his unique experience with both the legal and entrepreneurial worlds to CrowdCheck, allowing him to effectively address the needs of startups.

Brian R. Knight, Co-Founder and Vice President for Platform Services at CrowdCheck, has experience as both an attorney and an entrepreneur. Brian has served as an attorney in the private sector and for the Federal Government. He also started and ran Publius Incorporated, a business focused on improving constituent communications with elected officials. Brian brings his unique experience with both the legal and entrepreneurial worlds to CrowdCheck, allowing him to effectively address the needs of startups.

Prior to co-founding CrowdCheck, Brian worked out of the well-known Tech Ranch incubator in Austin, Texas on Publius. He merged Publius into Ballotbook Corp., where he served as General Counsel and Chief Operations Officer before leaving to work on CrowdCheck full time. Through this experience Brian fell in love with being an entrepreneur and gained firsthand insight into the challenges facing small businesses. Prior to moving to Austin, Brian served in the General Counsel’s office of the Central Intelligence Agency and with a firm specializing in commercial litigation.

Brian has a B.A. from the College of William and Mary and a J.D. from the University of Virginia School of Law. Brian is a member of the North Carolina Bar.