If you walk into any Whole Foods Market, you’ll see a stunning variety of produce — fruits and vegetables, meats and fish, bread and cheese — meticulously arranged, designed to inspire your appetite with their bounty. Look closely, and you’ll notice that some of this produce is labeled “organic,” and some is “conventional;” both of these terms are infused with deep cultural meaning. The distinction between conventional and organic is not just limited to food, however. It also explains a trend in the adoption of so-called “alternative” financial services. Over the past several years, non-bank lenders have captured an increasing portion of loan issuance in the United States and around the world; marketplace lenders are expected to reach potentially $500 billion in global volume by 2020. Given this dramatic shift in consumer and business funding, it makes sense to explore whether the “alternative” moniker still makes sense.

The term “conventional,” when applied to fruits and vegetables, is known as a retronym, a type of neologism used to differentiate the meaning of an existing word from its new meaning in the wake of technological advances (e.g., “acoustic guitars” used to just be called “guitars”; “manual transmissions” used to just be called “transmissions”). What, in fact, is conventional about “conventional produce?” The cultivation methods employed — monoculture planting, significant application of pesticides, and highly industrialized harvest — are actually historically anomalous, existing only for the past 100 years or so. Factory farming is quite new, and when viewed in a larger historical context, conventional agriculture is not conventional at all.

The same is true for “traditional banking.” The practice of conducting business through one of a handful of global mega-banks has, in fact, only existed for the past 150 years or so. From the emergence of currency, estimated by historians to have taken place several thousand years ago, to the establishment of banks, humans practiced what might today be called peer-to-peer lending, a term that itself could be considered a retronym, since at one point, this was just known as “lending.” Perhaps traditional banking is not so traditional after all.

The same is true for “traditional banking.” The practice of conducting business through one of a handful of global mega-banks has, in fact, only existed for the past 150 years or so. From the emergence of currency, estimated by historians to have taken place several thousand years ago, to the establishment of banks, humans practiced what might today be called peer-to-peer lending, a term that itself could be considered a retronym, since at one point, this was just known as “lending.” Perhaps traditional banking is not so traditional after all.

Why Industrialization?

In the realm of agriculture and food, what we now consider to be premium products were once a necessity subject to the constraints of the technology available at the time. “Local food,” for most of human history, was the only option, as the refrigeration, preservation, and long-distance transport that enable the modern food supply chain did not exist. “Seasonal food” was not a sought-after delicacy available at the trendiest farm-to-table restaurants, but rather the only option available. As recently as the 1990s, the term “imported” was used to confer an air of luxury upon an item on a menu, with the implication that the cost involved in supplying this item made it available to only an exclusive few.

In the realm of agriculture and food, what we now consider to be premium products were once a necessity subject to the constraints of the technology available at the time. “Local food,” for most of human history, was the only option, as the refrigeration, preservation, and long-distance transport that enable the modern food supply chain did not exist. “Seasonal food” was not a sought-after delicacy available at the trendiest farm-to-table restaurants, but rather the only option available. As recently as the 1990s, the term “imported” was used to confer an air of luxury upon an item on a menu, with the implication that the cost involved in supplying this item made it available to only an exclusive few.

A similar pattern can be found in the history of banking. Hundreds of years ago, peer-to-peer lending wasn’t a hot, booming area of fintech innovation. It was the only option! People needing to borrow money might have done so from a relative, a friend, or a local moneylender, but they almost certainly did not do so through a nationwide branch network of a fractional-reserve bank with access to the Federal Reserve discount window. Those taking the risk to lend money did so on the basis of personal trust and hard collateral, as there were no credit bureaus, FICO scores, or anything of the sort.

We have seen industrialized farming come under fire for its effects on the environment, its treatment of animals, and the potential inferiority of food bred for integrity during transport and maximization of yield rather than for taste or nutritional value. Conventional banking, of course, has its limits as well. While the industrialization of financial services powered a massive period of global economic growth which would not have been possible without it), this consolidation came at the expense of customer service, personalization, approachability, and capacity for innovation. Those costs can be seen in consumer attitudes. For example, 71% of the U.S. population under the age of 35 report significant frustration with large banks, saying that they would rather go to the dentist than visit a bank branch (a dubious statistic but illustrative nonetheless). In an age of ubiquitous, consumer-friendly mobile technology, customers expect to handle their financial affairs just as conveniently as they book an AirBnB, order an Uber, or click-to-buy on Amazon Prime.

We have seen industrialized farming come under fire for its effects on the environment, its treatment of animals, and the potential inferiority of food bred for integrity during transport and maximization of yield rather than for taste or nutritional value. Conventional banking, of course, has its limits as well. While the industrialization of financial services powered a massive period of global economic growth which would not have been possible without it), this consolidation came at the expense of customer service, personalization, approachability, and capacity for innovation. Those costs can be seen in consumer attitudes. For example, 71% of the U.S. population under the age of 35 report significant frustration with large banks, saying that they would rather go to the dentist than visit a bank branch (a dubious statistic but illustrative nonetheless). In an age of ubiquitous, consumer-friendly mobile technology, customers expect to handle their financial affairs just as conveniently as they book an AirBnB, order an Uber, or click-to-buy on Amazon Prime.

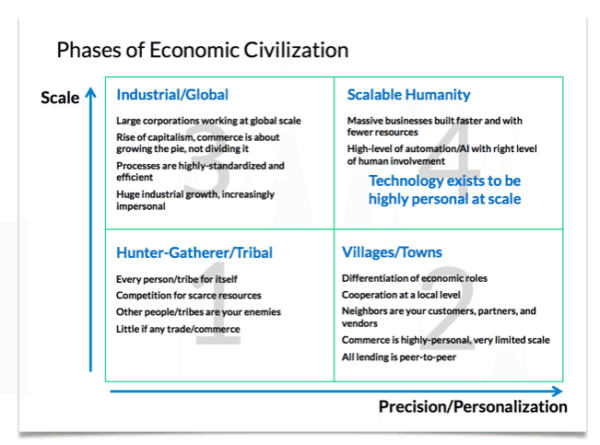

Scalable Humanity

Even if you find tempting the image of a grassroots system driven by small-scale borrowers and lenders, we live in a fast-paced, hyper-connected, multi-trillion dollar global economy, and there is no going back. Until very recently, the only way to achieve scale in a financial operation was through consolidated mega-banking. Now, only in the past 5 to 10 years, have we attained sufficiently powerful technology to offer highly personal service at a global scale.

With the rise of marketplace lending, consumers and businesses are no longer at the mercy of a handful of institutions offering highly similar products, as lending is not restricted to those who could build a branch, take deposits, and issue debt in the capital markets. A wide variety of new lenders have emerged, each offering more specific, more highly-tailored products to would-be borrowers. Because the technology now exists to rapidly fund these loans with a diverse pool of investors, a wider population of borrowers can obtain credit for a wider variety of needs.

There are now 8,268 farmers markets in the United States according to the USDA, having grown 180% since 2006. While we may have reached a peak in farmers markets, the organic banking revolution is just getting started. Marketplace lending in 2014 amounted to $12 billion in the U.S., a market estimated to reach $122 billion by 2020, according to a recent Morgan Stanley report. Like fruits and vegetables, organic banking thrives on sunlight and flourishes in an environment of transparency and trust. Today’s technology and the marketplace lending movement offer the promise of robust and sustainable growth without forsaking our literal or metaphorical roots.

As people and businesses have more diverse options, financial service providers, whether bank or non-bank, will have to work harder to demonstrate their value and offer a great customer experience. Because computers have become so efficient at tasks that are repeatable and standard, humans can now focus on things that are uniquely human. The more efficient allocation of capital enabled by marketplace lending will help millions of consumers and businesses improve their financial lives. It will lead to the creation of more small businesses, more new products, and more jobs. Marketplace lending has captured our attention not just for its big headlines and rapid growth, but for the promise of allowing our economy to scale with humanity.

As people and businesses have more diverse options, financial service providers, whether bank or non-bank, will have to work harder to demonstrate their value and offer a great customer experience. Because computers have become so efficient at tasks that are repeatable and standard, humans can now focus on things that are uniquely human. The more efficient allocation of capital enabled by marketplace lending will help millions of consumers and businesses improve their financial lives. It will lead to the creation of more small businesses, more new products, and more jobs. Marketplace lending has captured our attention not just for its big headlines and rapid growth, but for the promise of allowing our economy to scale with humanity.

David Snitkof is Chief Analytics Officer and co-founder of Orchard Platform. David has applied analytics and technology to banking, healthcare, travel, and media for over 10 years. At American Express, he worked on risk, product, and marketing analytics for new consumer card products and partnerships and also developed the underwriting criteria used to approve or decline billions of dollars in new credit. At Citigroup, David led a team driving analytics and strategy for the full Small Business credit lifecycle. David also was head of analytics and marketing at Oyster.com, an online travel startup since acquired by TripAdvisor. David excels at developing creative uses for data, communication of technical concepts, and building high-performing teams and products. He graduated from Brown University, where he studied Economics, Cognitive Psychology, & Neuroscience.

David Snitkof is Chief Analytics Officer and co-founder of Orchard Platform. David has applied analytics and technology to banking, healthcare, travel, and media for over 10 years. At American Express, he worked on risk, product, and marketing analytics for new consumer card products and partnerships and also developed the underwriting criteria used to approve or decline billions of dollars in new credit. At Citigroup, David led a team driving analytics and strategy for the full Small Business credit lifecycle. David also was head of analytics and marketing at Oyster.com, an online travel startup since acquired by TripAdvisor. David excels at developing creative uses for data, communication of technical concepts, and building high-performing teams and products. He graduated from Brown University, where he studied Economics, Cognitive Psychology, & Neuroscience.