First off, don’t panic. We’re not talking about hacking into computer networks or anything. Legal hacking, or hacking the law, doesn’t involve anything surreptitious. From an organization standpoint, Legal Hackers is an organization originating from  Brooklyn Law School and now a global movement with over thirty city chapters and thousands of members who convene to discuss and shape the future of the legal industry.

Brooklyn Law School and now a global movement with over thirty city chapters and thousands of members who convene to discuss and shape the future of the legal industry.

It is also a mindset. As Dan Lear explains in his American Bar Association article on legal hacking, legal hackers are “creative problem solvers, dedicated to finding efficiencies, making law more accessible, improving the law for lawyers and their clients, and disrupting outdated models in the legal system”. Oftentimes, legal hackers are, as Lea Rosen wrote, “committed to the practice of law, but find the dominant ethos of law practice unsatisfactory. At best, it doesn’t convey our reasons for studying the law; at worst, it represents everything we oppose: the perpetuation of lawyers as ‘conservative wallflowers and naysayers.’ In Jonathan Askin’s words:

‘We are “yeah, but” lawyers in a “why not?” world.’”

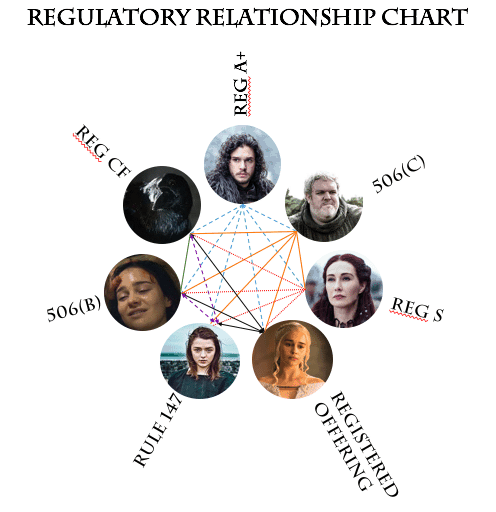

Crowdfunding law represents a unique opportunity to both innovate and shape a highly regulated industry via legal hacking. This article will focus on hacking crowdfunding law—specifically with respect to how to mix and match regulations (we call this “concurrent offerings” in legalese).

Concurrent Offerings 101

Before we get into the fun stuff, it’s worth taking some time to highlight and explain some important, overarching concepts when it comes to mixing and matching offering types.

Concurrent offerings: Concurrent means simultaneous. If two offerings are concurrent, then their investment period is either simultaneous, overlapping, or just close in time.

Integration: When an issuer mixes and matches regulations, one of the most important questions to ask is whether the securities sold are integrated—that is, whether two or more offerings should be considered to be, in fact, one offering. The integration doctrine seeks to prevent an issuer from improperly avoiding registration by artificially dividing a single offering into multiple offerings such that Securities Act exemptions would apply to the multiple offerings that would not be available for the combined offering. All offers that are part of the same, larger financing must qualify under an exemption, or none of them do. While the default presumption is that multiple similar offerings are integrated, five factors are relevant to the question of integration are whether:

(1) the different offerings are part of a single plan of financing,

(2) the offerings involve issuance of the same class of security,

(3) the offerings are made at or about the same time,

(4) the same type of consideration is to be received, and

(5) the offerings are made for the same general purpose.

If two offerings should be integrated, then it must satisfy the conditions of a single exemption. Failure to do so could lead to recession and a five-year ban from raising capital under the bad actor rules.

Solicitation Framework: Some regulations allow for general solicitation. That means the issuer can advertise the offering as much as they want, wherever they want, be it social media ads, billboards, or announcement at an event by megaphone (so long as they don’t make any misrepresentations, of course). Some regulations allow general solicitation, but with certain restrictions. Regulation CF, for example, allows general solicitation but prohibits issuers from advertising the terms of the security being sold. Other regulations do not allow general solicitation at all, meaning that an issuer’s investor pool may be limited to investors with whom they already have a substantial, pre-existing relationship.

One important consideration when mixing and matching concurrent offerings is to be wary when one regulation allows general solicitation while another does not. The SEC basically does not want an issuer to be able to have their cake and eat it too. Their concern centers around how investors in a private offering are solicited—whether by the offering that allows for general solicitation or through some other means. If investors in the private offering become interested in the private offering via general solicitation, then the exemption would not be available. If, however, investors in the private offering became interested through some other means—such as a substantive, pre-existing relationship between the investors and the company—then general solicitation was not used to lure investors, and use of the exemption would be available. Basically, the SEC is sensitive to issuers who try to use avenues of general solicitation available under one exemption to drum up investors and funnel them into another offering that does not allow for general solicitation. Additionally, if two offering types allow for general solicitation, but one type if more restrictive than the other (i.e. Rule 506(c) and Reg CF offering), the concurrent offering would generally be bound by the solicitation rules of the more restrictive offering type.

Economics: This is not a securities concept as much as it is plain common sense, but please-oh-please don’t mix and match regulations for the sake of trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. Sometimes it is possible, but the economics make no sense. I occasionally get calls from folks who spend time googling the law and come up with some novel idea about how to backend themselves into strange offering structures to try to achieve some goal (often one that the SEC wouldn’t want them to achieve). Even if not illegal, these schemes make little or no sense from a business perspective. All this is to say that issuers need to also take into account time and resources when figuring out their offering strategy. An offering that might raise a million dollars is no good if it took a million (or even half a million) dollars to offer.

Economics: This is not a securities concept as much as it is plain common sense, but please-oh-please don’t mix and match regulations for the sake of trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. Sometimes it is possible, but the economics make no sense. I occasionally get calls from folks who spend time googling the law and come up with some novel idea about how to backend themselves into strange offering structures to try to achieve some goal (often one that the SEC wouldn’t want them to achieve). Even if not illegal, these schemes make little or no sense from a business perspective. All this is to say that issuers need to also take into account time and resources when figuring out their offering strategy. An offering that might raise a million dollars is no good if it took a million (or even half a million) dollars to offer.

Now that we’ve reviewed the elementary concepts behind concurrent offerings (you know what that means now, right?), in Part 2, we’ll deep dive into specific examples of mixing and matching offerings.

Disclaimer: The following is for educational purposes only, and is not meant to be legal advice and should not be relied upon. You should consult with a securities attorney to assess the particular facts around your offering.

Amy Wan, Esq.CIPP/US, is a Senior Contributor to Crowdfund Insider. Amy is a Partner at Trowbridge Sidoti LLP (CrowdfundingLawyers.net) where she practices crowdfunding and syndication law. Formerly, she was General Counsel at Patch of Land, a real estate marketplace lending platform. While there, Amy pioneered the industry’s first payment dependent note that is secured pursuant to an indenture trustee and designed to be bankruptcy remote, and advised the company on its Series A funding round. In recognition her work at Patch, she was named as a Finalist for the Corporate Counsel of the Year Award 2015 by LA Business Journal. Amy also brings extensive experience in legal innovation and rethinking the delivery of legal services. She is the founder and co-organized of Legal Hackers LA, and was named one of the one of ten women to watch in legal technology by the American Bar Association Journal in 2014.

Amy Wan, Esq.CIPP/US, is a Senior Contributor to Crowdfund Insider. Amy is a Partner at Trowbridge Sidoti LLP (CrowdfundingLawyers.net) where she practices crowdfunding and syndication law. Formerly, she was General Counsel at Patch of Land, a real estate marketplace lending platform. While there, Amy pioneered the industry’s first payment dependent note that is secured pursuant to an indenture trustee and designed to be bankruptcy remote, and advised the company on its Series A funding round. In recognition her work at Patch, she was named as a Finalist for the Corporate Counsel of the Year Award 2015 by LA Business Journal. Amy also brings extensive experience in legal innovation and rethinking the delivery of legal services. She is the founder and co-organized of Legal Hackers LA, and was named one of the one of ten women to watch in legal technology by the American Bar Association Journal in 2014.