Passed with large bipartisan majorities and signed into law by President Obama, the 2012 JOBS Act was a bipartisan achievement of consequence. The JOBS Act substantially improved the laws governing entrepreneurial capital formation and has had a measurable positive impact on entrepreneurial capital formation. But it was just a beginning. Ten years have passed with relatively little action improving the laws governing entrepreneurial capital formation. More needs to be done.

On the 10th anniversary of the JOBS Act, Senate Banking Committee Republicans under Sen. Toomey’s leadership, have released a discussion draft of new legislation, called JOBS Act 4.0, that would considerably improve the regulatory environment for entrepreneurs seeking to raise capital. In all, it contains 29 discrete pieces of legislation, many of which have also been introduced as stand-alone legislation. The package, considered as a whole, can be expected to have a very positive impact comparable to that of the original JOBS Act. These bills were discussed at an April 5th Senate Banking Committee hearing at which the author testified.

Sen. Toomey is seeking public comments on how the draft legislation may be improved by June 3, 2020. Comments may be provided by email to submissions@banking.senate.gov.

The discussion draft is divided into four titles:

Title I—Encouraging Companies to be Publicly Traded (8 sections)

Title II—Improving the Market for Private Capital (6 sections)

Title III—Enhancing Retail Investor Access to Investment Opportunities (8 sections)

Title IV—Improving Regulatory Oversight (7 sections)

The discussion below addresses 15 of the bills included in the discussion draft. All bill numbers refer to the 117th Congress unless otherwise noted.

The Impact of the Original JOBS Act

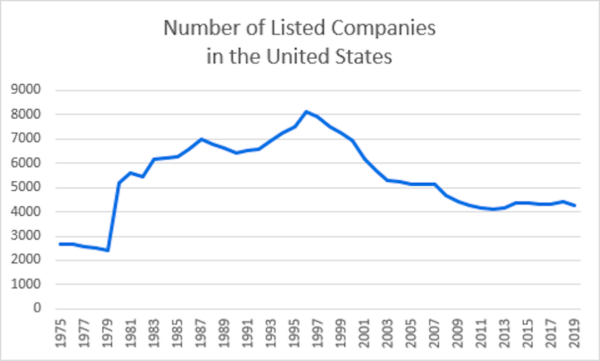

In all, as the tables below show, JOBS Act offerings amounted to about three to seven percent of the private capital raised in the U.S. in 2018 and 2019. The Title I Emerging Growth Company (EGC) provisions account for additional capital raised (although this capital is raised in the public market). The graph below showing the number of listed companies is quite remarkable. The number of public companies was in a free fall prior to the JOBS Act. Now that number is basically flat. The number of IPOs in the nine years after the JOBS Act has increased by 43 percent relative to the nine years before the JOBS Act and the amount raised has increased by 57 percent. Precisely how much of that is attributable to Title I is not clear but roughly four-fifths of issuers conducting IPOs appear to be taking advantage of EGC status.

Amounts Raised in the Exempt Market in 2018 ($ billions); Amount Raised by Exemption; Number of IPOs Pre-post JOBS Act

|

Exemption |

Amount Raised |

Percentage of Total |

|

Rule 506(b) of Regulation D |

$ 1,500 |

51.48% |

|

Rule 506(c) of Regulation D |

$ 211 |

7.24% |

|

Rule 504 of Regulation D |

$ 2 |

0.07% |

|

Regulation D Subtotal |

$ 1,713 |

58.79% |

|

Regulation A: Tier 1 |

$ 0.061 |

0.00% |

|

Regulation A: Tier 2 |

$ 0.675 |

0.02% |

|

Regulation A Subtotal |

$ 0.736 |

0.03% |

|

Regulation Crowdfunding; Section 4(a)(6) |

$ 0.055 |

0.00% |

|

Other exempt offerings |

$ 1,200 |

41.18% |

|

Total |

$ 2,913.791 |

100.00% |

|

JOBS Act Offerings |

$ 211.791 |

7.27% |

|

Exemption |

Amount Raised |

Percentage of Total |

|

Rule 506(b) of Regulation D |

$ 1,492 |

54.73% |

|

Rule 506(c) of Regulation D |

$ 66 |

2.42% |

|

Rule 504 of Regulation D |

$ 0.228 |

0.01% |

|

Regulation D Subtotal |

$ 1,558.228 |

57.15% |

|

Regulation A: Tier 1 |

$ 0.044 |

0.00% |

|

Regulation A: Tier 2 |

$ 0.998 |

0.04% |

|

Regulation A Subtotal |

$ 1.042 |

0.04% |

|

Regulation Crowdfunding |

$ 0.062 |

0.00% |

|

Other exempt offerings |

$ 1,167 |

42.80% |

|

Total |

$ 2,726.332 |

100.00% |

|

JOBS Act Offerings |

$ 67.104 |

2.46% |

| Year | Number of IPOs | Aggregate Proceeds ($ billions) |

| 2004 | 173 | $31 |

| 2005 | 159 | $28 |

| 2006 | 157 | $30 |

| 2007 | 159 | $36 |

| 2008 | 21 | $23 |

| 2009 | 41 | $13 |

| 2010 | 91 | $30 |

| 2011 | 81 | $27 |

| 2012 | 93 | $31 |

| 2013 | 158 | $42 |

| 2014 | 206 | $42 |

| 2015 | 118 | $22 |

| 2016 | 75 | $13 |

| 2017 | 106 | $23 |

| 2018 | 134 | $33 |

| 2019 | 112 | $39 |

| 2020 | 165 | $62 |

| 2021 | 311 | $119 |

| 2004-2012 (Average) | 108 | $28 |

| 2013-2021 (Average) | 154 | $44 |

1. Sec. 102: Emerging Growth Company Extension Act.

Title I of the JOBS Act created the Emerging Growth Company (EGC) status to reduce the cost of initial public offerings and of early continuing compliance costs. This aspect of the JOBS Act appears to have been a significant success. The number of IPOs has been trending upwards and roughly four-fifths of issuers conducting IPOs appear to be taking advantage of EGC status. The number of IPOs in the nine years after the JOBS Act has increased by 43 percent relative to the nine years before the JOBS Act and the amount raised has increased by 57 percent.

Nevertheless, the number of IPOs is still dramatically fewer than in the 1990s and the amounts raised, particularly when adjusted for inflation, are not impressive. IPOs are barely keeping pace with exits (either through mergers, delisting due to financial failure or going private transactions).

The EGC provisions of JOBS Act 4.0 would extend the period that a company could retain its Emerging Growth Company status from five to ten years. This would reduce the cost of being a public company until substantial size or maturity is achieved and will, therefore, make IPOs more attractive. It is part of a well-conceived scaled disclosure regime.

The ever-increasing regulatory burden on public companies means that companies are going public much later in their life cycle. This, in turn, means that a disproportionate share of the gains from successful entrepreneurial ventures accrues to accredited investors buying private placements rather than ordinary investors who own publicly traded shares. Policymakers should seek to reduce the burden on public companies so that ordinary American investors can share in these gains.

The discussion draft could be improved in two ways. First, EGC status should be made indefinite rather than limiting it to 10 years. Second, the Securities Act and the Securities Exchange Act should be amended so that EGCs (and smaller reporting companies) are exempt from (1) climate change or greenhouse gas emissions reporting, (2) diversity, equity, and inclusion reporting and (3) human capital management reporting (all of which are in the SEC regulatory pipeline). Of course, it would be preferable to simply define materiality so that such reporting is not required of any issuer.

The proposed climate change rule alone has been estimated by the SEC to increase the costs of being a public company by an astounding 165 percent, by $6.38 billion in the aggregate from $3.86 billion to $10.24 billion. And this is a massive underestimate because huge swaths of the costs imposed by scope 3 are not counted. In other words, the proposed climate change rule will nearly triple the costs of being a public company. With one regulation, the Commission is considering adding more costs on issuers than all of the regulations promulgated in the previous nine decades. It is difficult to conceive of a more destructive policy and, if promulgated, it will dwarf the positive impact of this legislation. The DEI and human capital management reporting requirements will just make the problem worse. The SEC climate change, DEI, and human capital management rules can be expected to radically reduce the number of IPOs and to cause a large number of “going private” transactions among small and medium-sized issuers.

2. Sec. 103: Dodd-Frank Material Disclosure Improvement Act (S.3923).

This important bill, introduced by Sen. Cramer, would repeal the conflict minerals, mine safety, resource extraction, and pay ratio provisions in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Specifically, it would repeal section 953 (relating to executive compensation and so-called “pay versus performance”), section 1502 (relating to conflict minerals), section 1503 (relating to coal or other mine safety), or section 1504 (relating to resource extraction). These provisions are extremely expensive for issuers to comply with and provide no material information to investors seeking to make investment decisions. They are politically motivated disclosure requirements. This bill would make a substantial contribution to the effort to reducing the cost of being a public company and be an important step to reorienting securities laws toward their fundamental purpose of providing investors with information material for their investment decisions.

3. Sec. 107: The Main Street Growth Act (S.3097).

Improving the secondary markets for small capitalization firms would help investors achieve a higher return and reduce risk, improve entrepreneurs’ access to capital and promote innovation, economic growth and prosperity.

There are three key steps to improving secondary markets for small firms. First, improve the regulatory environment for existing non-exchange over-the-counter (OTC) securities traded on alternative trading systems (ATSs), primarily by (a) providing the same reduced blue sky burden that large companies whose securities trade on exchanges currently enjoy, (b) re-establishing the list of marginable OTC securities and (c) removing impediments to market-making caused by Regulation SHO.

Second, improve the regulatory environment for secondary sales of private securities (Regulation D and other private securities), primarily by codifying the so-called section 4(a)(1-1/2) exemption and ensuring that platform traded securities are eligible for the exemption. JOBS Act 201(c) and Securities Act section 4(a)(7) and section 4(d) are attempts to address this problem. They need, however, serious improvement and simplification. Third, amend the Securities Exchange Act to establish venture exchanges. All of these should be incorporated into JOBS Act 4.0.

The Main Street Growth Act, introduced by Sen. Kennedy, seeks to accomplish the third step by creating venture exchanges. Venture exchanges could prove to be a significant step towards promoting liquidity in the secondary market for relatively small issuers and, therefore, help investors in these companies achieve fair value for their securities when they choose to sell them. The Canadian TSX Venture Exchange and the United Kingdom’s Alternative Investment Market appear to be working well but have undergone some adjustments over time. These markets appear to have had a positive economic impact in the U.K. and Canada. There are at least a dozen similar but smaller markets in various countries around the world.

Two modifications are necessary to ‘The Main Street Growth Act’ if venture exchanges are going to achieve their potential. A third is advisable.

For venture exchanges to work well and achieve their promise, securities traded on a venture exchange must be covered securities within the meaning of Securities Act section 18(b) (15 USC 77r(b)). Requiring issuers to comply with every (or virtually every) state blue sky registration and qualification law as a condition of listing a security would be extremely costly. The issuer would have to do this because, unlike in a primary offering, they will not know the residence of people that may buy their security on the venture exchange. In principle, since venture exchanges under the bill are a subset of national securities exchange under proposed Securities Act section 6(m)(2)(A), they would be under existing Securities Act section 18(b)(1)(A). But proposed Securities Act section 18(d) in the bill (at section 2(b) of the bill) undoes that. This is a potentially devastating provision in the legislation that may well entirely upend the aims of the bill were it to be enacted in its present form. It certainly will make venture exchanges much less attractive to issuers. It should be removed.

Proposed Securities Act section 6 (m)(7) (relating to disclosures to investors trading on venture exchanges) also seems problematic for two reasons. First, it is not clear what kind of disclosures would be necessary. What are ‘characteristics unique to venture exchanges’ that investors should be worried about? I do not know but I am sure that the SEC will think of something.

Moreover, it is not clear to me how that would be done in practice. Most of these trades will occur electronically. Are we going to require that a broker-dealer provide a special pop-up window on customers’ desktop requiring them to read, or at least claim that they have read, a disclosure document every time a customer wants to trade a security that happens to be listed on a venture exchange? This is certainly one way to make venture exchanges less attractive.

Earlier versions of this legislation identified specific provisions in Regulation NMS that would not apply to venture exchanges. That would seem advisable. It is unlikely that the SEC will make decisions that are consistent with venture exchanges being an unqualified success. Congress needs to make the decisions if it wants venture exchanges to work.

4. Sec. 202: Expanding American Entrepreneurship Act (S.3976).

This constructive bill, introduced by Sen. Moran, would amend the Investment Company Act such that qualifying venture capital funds could have aggregate capital contributions of $50 million rather than $10 million and increase the number of permitted beneficial owners from 250 to 500. It can be expected to increase the amount of capital available to entrepreneurs and to reduce the costs of providing them with capital. It will, therefore, have a positive economic impact.

5. Sec 204: Small Entrepreneurs’ Empowerment and Development (SEED) Act (S.3939).

This important bill, introduced by Sen. Scott, is needed legislation. It would relieve the smallest businesses from having to worry about the complexity of the securities laws. It is simple, straight-forward, and does the job.

Specifically, the bill would exempt from registration requirements any issuer that sells less than $500,000 in securities of any type within a 12-month period and treat those securities as ‘covered securities” thereby protecting against onerous state blue sky laws. It would make the exemption unavailable to certain designated bad actors. I have long been a strong proponent of this kind of exemption.

Every business in the country should not be roped into dealing with the securities laws and the SEC or the state equivalent. Some businesses are private enough, closely held enough and small enough that, absent fraud, the SEC or state securities regulators simply should not be involved. That is the point of this exemption. Any such exemption should contain bright lines that non-specialists can read and be sure that these businesses are okay. S. 3939 meets that test.

6. Sec. 205: Unlocking Capital for Small Businesses Act (S.3922).

This important bill, introduced by Sen. Cramer, would help a great many small businesses that operate outside of affluent major metropolitan areas to find capital with the aid of finders and private placement brokers. It is important, well-drafted legislation that addresses a major problem that is under-appreciated in Washington. It would help the smallest entrepreneurs access capital found in money centers. It is hard to estimate the number of businesses that would be helped by this legislation but it will probably be in the many tens of thousands annually and potentially over a hundred thousand each year once it has been law for a reasonable period. The bill would reverse two decades of irresponsible policies pursued by the SEC.

A “finder” is a person who is paid to assist small businesses to find capital from time to time by making introductions to investors. Usually, finders operate in the context of some other business (e.g., the practice of law, public accounting, insurance brokerage, etc.), as a Main Street business colleague or acquaintance, or as a friend or family member of the business owner. They are sometimes called private placement brokers, although this term is probably best used to describe people that are in the business of making introductions between investors and businesses. They are typically paid a small percentage of the amount of capital that they helped the business owner to raise.

Finders play an important role in introducing entrepreneurs to potential investors, thus helping them to raise the capital necessary to launch or grow their businesses. For regulatory purposes, neither finders nor private placement brokers should be treated the same as Wall Street investment banks (i.e., a large, registered broker-dealer). A business owner should be able to compensate people for helping him or her to find and raise capital. He should be able to offer, for example, a 2 percent finders’ fee to those that help him identify investors. In the real world, people respond to incentives, and being able to offer a financial reward will make people more willing to take the time and effort necessary to help small business owners find the capital that they need.

In large metropolitan areas like New York, Washington, or San Francisco, there are many accredited investors and most entrepreneurs in those cities will know many accredited investors. There are also large informal networks of such investors. In the Midwest, South, and Rocky Mountain West (with the exception of a few large cities) and in less developed rural areas throughout the country, accredited investors are few and far between. Most entrepreneurs in these regions will only know a few accredited investors and informal investor networks do not exist or are very small. Finders represent an opportunity to enable entrepreneurs in these regions to find accredited investors from outside of their communities.

The current legal status of finders is a morass. It is a morass created by the Commission. It withdrew the guidance governing finders, various officials gave a series of speeches indicating that finders were probably unregistered broker-dealers, no additional guidance or rulemaking was forthcoming and selective regulation by enforcement was undertaken.

The Commission articulated the view that even those tangentially involved in a transaction were finders, especially if they took “transaction-based compensation” or, in other words, if they took compensation for actually doing what they said they would do. This is not only bad public policy but significantly beyond the scope of the statutory definition of a broker, to wit, “any person engaged in the business of effecting transactions in securities for the account of others.”

After two decades of procrastination and neglect by the Commission and its staff, the Commission in October of 2020 proposed an exemptive order that would have improved the existing situation. The proposed exemptive order is, however, markedly too narrow regarding the proposed Tier I finders category and should be improved. In any event, the current Commission is unlikely to move forwards. Entrepreneurs cannot afford to wait another two decades for this problem to be favorably resolved by the Commission. Congress should Act.

7. Sec. 206: Small Business Mergers, Acquisitions, Sales, and Brokerage Simplification Act (S.3391).

This constructive bill, introduced by Sen. Kennedy, would substantially mitigate a long-standing problem. It would exempt certain M&A Brokers from the requirement to register as a broker-dealer subject to limitations on their activities.

Business brokers make the market for closely held small businesses more efficient, by helping entrepreneurs to sell their business for full value and by helping aspiring business owners find business opportunities that match their skills and financial resources. Although, after many years of delay, the Securities and Exchange Commission issued a 2014 a no-action letter that improves the situation, its position on who should be required to register as a securities broker-dealer remains overbroad and significantly exceeds the scope of the statutory requirement. Complying with the requirements of the no-action letter is far from simple.

The preferred solution is for business brokers helping to buy and sell small businesses to simply be exempt from the broker-dealer registration requirements. This bill is a major step in that direction. In 2017, the House unanimously passed the “Small Business Mergers, Acquisitions, Sales, and Brokerage Simplification Act.” The Senate has failed to do so.

8. Sec. 301: Small Business Audit Correction Act (H.R.8983 S.2724, 116th Congress).

The number of broker-dealers has declined by about 30 percent over the past 15 years. A large reason for this decline is the ever-increasing regulatory burden that crushes the profitability of small broker-dealers. Regulatory costs do not increase linearly with size, so heavy regulation accords a competitive advantage to large firms. The decline in small broker-dealers harms small entrepreneurs because small broker-dealers are more likely to assist them to raise capital than large investment banks.

This constructive bill would exempt privately-held, non-custodial broker-dealers from the requirements to use a Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) registered firm for their audits. These small firms are not public companies and do not hold customer securities or funds. They pose no risk to the financial system as a whole. It is appropriate to allow them to comply only with normal audits rather than the more expensive PCAOB compliant audits. They would still be subject to the full panoply of both SEC and FINRA rules governing broker-dealers.

9. Sec. 303: Gig Worker Equity Compensation Act (S.3931).

This constructive although potentially overbroad bill, introduced by Sen. Lummis, would extend Rule 701 provisions relating to compensatory benefit plans to “individuals (other than employees) providing goods for sale, labor, or services for remuneration to an issuer, or to customers of an issuer, to the same extent as that exemption applies to employees of the issuer.”

Allowing independent contractors or “gig workers” to share in the financial success of the issuer that they work for and allowing the issuer to align their incentives with those of the issuer by providing securities to the workers is laudable and deserves support. It is not clear to me that it is advisable to extend Rule 701 to customers of an issuer (as the bill does).

10. Sec. 304: – Increasing Investor Opportunities Act (S.3948).

This constructive bill could potentially have a significant positive impact on non-accredited investor returns by giving them access to professionally managed funds that invest in private offerings.

11. Sec. 305: Improving Crowdfunding Opportunities Act (S.3967).

This constructive bill, introduced by Sen. Moran, would make significant improvements to crowdfunding, particularly the regulation of funding portals. It would broaden blue sky preemption, reverse a badly conceived SEC interpretation of its Regulation CF that treats crowdfunding portals as issuers for liability purposes, limits the Bank Secrecy Act requirements for funding portal requirements since funding portals are prohibited from holding customer funds by law and the investor funds held by banks are fully subject to AML-CFT Bank Secrecy Act requirements, and explicitly permit impersonal investment advice that does not purport to meet the objectives or needs of a specific individual or account. All of these are very helpful and will improve the attractiveness of crowdfunding. Given, however, the complexity and burden that Congress and then the SEC added to Title III, Congress should also consider whether more fundamental reforms will be necessary for equity crowdfunding to fulfill its promise.

12. Sec. 306: Equal Opportunity for all Investors Act (S.3921).

Regulation D investments are generally restricted to accredited investors, who are affluent individuals or institutions. The vast majority of Americans are effectively prohibited from investing in Regulation D securities. The SEC currently estimates that only about 16 million households (13 percent of the total) qualify as accredited. Companies are going public much later than in the past, so those who invest in private offerings generally receive a higher share of the returns generated by successful entrepreneurial ventures than those who invest in relatively late-stage public companies. Congress should democratize access to these private offerings so that they are available to more investors.

This important bill, introduced by Sen. Tillis, would substantially democratize access to Regulation D private placements. It would allow people to test into accredited investor status by demonstrating their knowledge of investing. It would generally permit self-certification by investors as to whether they meet income or net worth requirements in all Rule 506 offerings. This is a particular step forward for Rule 506(c) offerings. Any natural person with at least $500,000 worth of investments would qualify. Any person investing no more than (a) 10 percent of the total investments of the person; (b) 10 percent of the annual income of the person or 10 percent of the annual combined income with that person’s spouse; or (c) 10 percent of the net worth of the person excluding the value of the person’s principal place of residence in private offerings would qualify. It would give millions of people access to Regulation D private offerings that are currently generally barred from investing in those offerings. Additional professional certification or educational attainment criteria could be added.

The final rule implementing Title II of the JOBS Act created a safe harbor that inevitably, in practice, became the rule. Thus, “reasonable steps to verify” requirement for what became Rule 506(c) effectively means obtaining tax returns or comprehensive financial data proving net worth. Many investors are reluctant to provide such sensitive information to issuers with whom they have no relationship as the price of making an investment and, given the potential liability, accountants, lawyers and broker-dealers are unlikely to make certifications except perhaps for very large, lucrative clients. Issuers seek to avoid the compliance costs and regulatory risks.

Self-certification is the general, accepted practice for what is now known as Rule 506(b) offerings. That has been the case since the advent of Regulation D. Self-certification should be allowed for all Rule 506 offerings and obtaining an investor self-certification should be deemed to constitute taking “reasonable steps to verify that purchasers of the securities are accredited investors” as required by the JOBS Act. This is what the Equal Opportunity for all Investors Act does.

Self-certification is permitted in the United Kingdom both for sophisticated investors and high net worth investors (income of £100,000 or more or net assets of £250,000 or more). Neither in the U.K. nor in 506(b) offerings (before and after the JOBS Act) has self-certification caused significant problems. The current 506(c) rules are a solution addressing a non-existent problem.

13. Sec. 307: Facilitating Main Street Offerings Act (S.3966).

About $1 billion dollars annually is now raised using Regulation A. It could and should be much more important.

One of the biggest things impeding the use of Regulation A is the fact that state blue sky laws are, under the Commission’s implementing rule, preempted only with respect to Tier 2 primary offerings. All Tier 1 and Tier 2 secondary offerings are still subject to blue sky laws. NASAA’s coordinated review program is an unmitigated failure and should be acknowledged as such.

This important bill, introduced by Sen. Moran, is meant to preempt blue sky laws for primary and secondary market for Regulation A Tier 2 securities. This would enable robust secondary markets in Regulation A securities to develop that would make Regulation A securities more liquid and enable investors to achieve better value when they sell their securities. It would also make primary offerings easier because investors buying from the issuer will know that they will be more easily able to sell their securities when they wish to do so. I am concerned, however, that the language in the bill does not do the job it is meant to do. It needs to be improved.

14. Sec. 404: Protecting Investors’ Personally Identifiable Information Act (S.1209).

The SEC mandated consolidated audit trail—or “CAT” requires broker-dealers to report securities transactions to CAT NMS LLC, a Delaware-based limited-liability company. The requirement invades investor privacy, creates a severe risk of data breaches, and will likely lead to more small firms leaving the financial services industry. CAT should be terminated.

This bill requires the Commission to specifically request personally identifiable information (PII) from CAT, thereby prohibiting requirements that CAT provide the commission bulk PII. Any PII provided to the Commission pursuant to a request must be destroyed by the Commission “not later than 1 day after the date on which the investigation or other matter for which that personally identifiable information is required concludes.” This will make it less likely that the information will be hacked since PII will only be in one database, not two, and the Commission has a poor data security record.

15. Sec. 405: Administrative Enforcement Fairness Act (S.3930).

Serious questions have been raised about the neutrality and impartiality of SEC administrative law judges (ALJs). According to the Wall Street Journal, during FY 2011–2014, the SEC prevailed in between 80 percent and 100 percent of cases in its own administrative law courts, depending on the year, but it prevailed in well under 75 percent of cases in federal court. Similarly, serious questions have been raised about whether procedural due process is adequately provided in the SEC’s in-house administrative law courts.

By allowing respondents to elect whether the adjudication occurs in the SEC’s administrative law court or an ordinary Article III federal court, those respondents who are concerned about the fairness of the SEC proceedings can choose to proceed in a federal district court. Section 823 of the House-passed Financial Choice Act would have made this change. This bill would as well.

Additional Proposals Relating to Entrepreneurial Capital Formation That Should be Added to JOBS Act 4.0.

Proposals Relating to Substantive Changes to the Securities Laws

1. Congress should codify and broaden the exemption from the section 12(g) holder-of-record limitations for Regulation A securities.

2. Congress should eliminate the income and net worth limitations imposed by Regulation A. These were not imposed by Securities Act section 3(b).

3. Congress should exempt P2P lending from federal and state securities laws.

4. Congress should amend Title III of the JOBS Act to create a category of crowdfunding security called a “crowdfunding debt security” or “peer-to-peer debt security” with lesser continuing reporting obligations.

5. Congress should statutorily define materiality in terms generally consonant with Supreme Court holdings on the issue but should specifically exclude social, ideological, or political objectives unrelated to investors’ financial, economic or pecuniary objectives.

6. Congress should amend the Securities Act and the Securities Exchange Act to reflect the principles of the Civil Rights Act by prohibiting securities regulators, including SROs, from promulgating rules or taking other actions that discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin of such individual or group. Legal discrimination or quotas on the basis of race or sex should be a relic of the past.

7. Congress should terminate the Consolidated Audit Trail program

Proposals Relating to Studies or Data Improvement

1. Congress should require the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis at the SEC to conduct a study mapping and reporting accredited investor data by state and county but permitting the use of core-based statistical areas or metropolitan statistical areas if data masking by the Census Bureau or the IRS Statistics of Income effectively requires their use.

2. Congress should require the SEC to publish better data on securities offerings, securities markets and securities law enforcement and to publish an annual data book of time series data on these matters (as outlined below). The Division of Economic and Risk Analysis (DERA) should publish annual data on:

(1) the number of offerings and offering amounts by type (including type of issuer, type of security and exemption used);

(2) ongoing and offering compliance costs by size and type of firm and by exemption used or registered status (e.g. emerging growth company, smaller reporting company, fully reporting company) including both offering costs and the cost of ongoing compliance;

(3) enforcement (by the SEC, state regulators and SROs), including the type and number of violations, the type and number of violators and the amount of money involved;

(4) basic market statistics such as market capitalization by type of issuer and type of security; the number of reporting companies, Regulation A issuers, crowdfunding issuers and the like; trading volumes by exchange or ATS; and

(5) market participants, including the number and, if relevant, size of broker-dealers, registered representatives, exchanges, alternative trading systems, investment companies, registered investment advisors and other information.

This data should be presented in time series over multiple years (including prior years to the extent possible) so that trends can be determined.

3. Congress should require an annual SEC and one-time GAO study that collects and reports data from state regulators on the fees or taxes they collect from issuers. These studies should collect data from at least the years 2017-2021 and classify the fees and taxes collected from issuers by offering type.

4. Congress should require an SEC study reporting the annual costs relating to Sarbanes-Oxley internal control reporting and the amounts paid by issuers each year to accounting firms in connection with compliance.

5. If the SEC promulgates the climate change/greenhouse gas emissions rule it has proposed, a DEI rule or a human capital management rule, Congress should require an SEC study reporting the annual costs of each of those rules.

David R. Burton focuses on tax matters, securities law, entrepreneurship, financial privacy and regulatory and administrative law issues as The Heritage Foundation’s senior fellow in economic policy. Burton was general counsel at the National Small Business Association for two years before joining Heritage’s Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies in 2013. He previously was Chief Financial Officer and general counsel of the start-up Alliance for Retirement Prosperity, a conservative alternative to AARP. For 15 years, Burton was a partner in the Argus Group, a Virginia-based law, public policy and government relations firm. His career in financial and tax matters also includes the posts of vice president for finance and general counsel of New England Machinery, a multinational manufacturer of packaging equipment and testing instruments, and manager of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Tax Policy Center. Burton received a Juris Doctor degree from the University Of Maryland School Of Law. He also holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics from the University of Chicago.

David R. Burton focuses on tax matters, securities law, entrepreneurship, financial privacy and regulatory and administrative law issues as The Heritage Foundation’s senior fellow in economic policy. Burton was general counsel at the National Small Business Association for two years before joining Heritage’s Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies in 2013. He previously was Chief Financial Officer and general counsel of the start-up Alliance for Retirement Prosperity, a conservative alternative to AARP. For 15 years, Burton was a partner in the Argus Group, a Virginia-based law, public policy and government relations firm. His career in financial and tax matters also includes the posts of vice president for finance and general counsel of New England Machinery, a multinational manufacturer of packaging equipment and testing instruments, and manager of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Tax Policy Center. Burton received a Juris Doctor degree from the University Of Maryland School Of Law. He also holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics from the University of Chicago.