In June 14 comments before the “Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit: Crypto,” William Hinman, Director of the SEC’s Division of Corporate Finance, stated:

- ETHER is not a security

- Decentralization and means of promotion are key to determining whether a token is a security.

- A digital asset originally classified as a security can “morph” into another type of asset.

- There are factors that would support the argument that a token is more a “consumer item” than a security.

- Tokens issued upon conversion of SAFTs may still be securities.

- The SEC strongly invites issuers to consult with them.

Introduction

Less than a month after the SEC launched its parody HoweyCoins website for investor education, William Hinman, Director of the SEC’s Division of Corporate Finance addressed the “Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit: Crypto” with remarks under the equally humorous title “Digital Asset Transactions: When Howey Met Gary (Plastic).” The remarks were an important development for the ICO ecosystem, which has to a significant extent been frozen by critical comments by SEC Chairman Jay Clayton.

Less than a month after the SEC launched its parody HoweyCoins website for investor education, William Hinman, Director of the SEC’s Division of Corporate Finance addressed the “Yahoo Finance All Markets Summit: Crypto” with remarks under the equally humorous title “Digital Asset Transactions: When Howey Met Gary (Plastic).” The remarks were an important development for the ICO ecosystem, which has to a significant extent been frozen by critical comments by SEC Chairman Jay Clayton.

Much of the initial press coverage of Mr. Hinman’s remarks focused on his declaration that Ether, the cryptocurrency of the Ethereum blockchain, was not a security. Mr. Hinman clearly answered this question, stating:

“…putting aside the fundraising that accompanied the creation of Ether, based on my understanding of the present state of Ether, the Ethereum network and its decentralized structure, current offers and sales of Ether are not securities transactions. And, as with Bitcoin, applying the disclosure regime of the federal securities laws to current transactions in Ether would seem to add little value.”

This paper will summarize Director Hinman’s analysis of Ether and digital token sales. However, there are two things should be kept in mind.

First, Hinman spoke in his individual capacity and the remarks do not reflect SEC rulemaking. However, as the director of a division within the SEC that has assumed a critical role in ICO regulation, it seems reasonable to assume that Hinman’s comments provide a window into the agency’s thinking.

First, Hinman spoke in his individual capacity and the remarks do not reflect SEC rulemaking. However, as the director of a division within the SEC that has assumed a critical role in ICO regulation, it seems reasonable to assume that Hinman’s comments provide a window into the agency’s thinking.

Second, these are remarks and understandably lack the refinement of legislation and rules. As a result, one should be cautious in drawing conclusions from nuances in the language of the remarks.

While the Howey case referenced in the title of the remarks has received near legendary status in the ICO community, the title calls attention to the lesser known Second Circuit decision in Gary Plastic Packaging Corp. v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 756 F.2d 230 (2d Cir. 1985).

There, the Court held that when a CD, exempt from being treated as a security under Section 3 of the Securities Act, is “sold as a part of a program organized by a broker who offers retail investors promises of liquidity and the potential to profit from changes in interest rates … the instrument can be part of an investment contract that is a security.”

The title of the remarks neatly bookended the SEC’s two principal ICO-related announcements — the DAO Report of Investigation (which relied heavily on the Howey criteria in finding the DAO tokens to be securities) and Munchee Inc.’s MUN tokens which were the subject of an SEC cease and desist order (while this decision also applied Howey, it gave significant weight to the manner in which sales of the MUN tokens were promoted, although the order did not cite Gary).

A commentator at Coincenter accurately termed this analysis of Munchee and Gary — “guilt by marketing association.”

The Issue

Director Hinman observed:

“The digital asset itself is simply code. But the way it is sold — as part of an investment; to non-users; by promoters to develop the enterprise — can be, and, in that context, most often is, a security — because it evidences an investment contract.”

He then posited the following question:

“Can a digital asset offered as a security can, over time, become something other than a security?”

Subject to certain conditions, his answer appears to be “yes,” unless the digital asset represents a financial interest in the issuer.

Analysis

Third Party Efforts Drive the Expectation of Return

Director Hinman indicated that the primary consideration in determining whether a digital asset is offered as an investment contract and is therefore a security, is whether “a third party — be it a person, entity or coordinated group of actors — drives the expectation of a return.”

This focus on third party involvement reflects major public policy concerns. As Hinman noted “…learning material information about the third party — its background, financing, plans, financial stake and so forth — is a prerequisite to making an informed investment decision. Without a regulatory framework that promotes disclosure of what the third party alone knows of these topics and the risks associated with the venture, investors will be uninformed and are at risk.”

Stressing that this is a “facts and circumstances” analysis, he provided illustrative examples of situations when a third party’s efforts is driving the return expectation:

1. Is there a person or group that has sponsored or promoted the creation and sale of the digital asset, the efforts of whom play a significant role in the development and maintenance of the asset and its potential increase in value?

2. Has this person or group retained a stake or other interest in the digital asset such that it would be motivated to expend efforts to cause an increase in value in the digital asset? Would purchasers reasonably believe such efforts will be undertaken and may result in a return on their investment in the digital asset?

3. Has the promoter raised an amount of funds in excess of what may be needed to establish a functional network, and, if so, has it indicated how those funds may be used to support the value of the tokens or to increase the value of the enterprise? Does the promoter continue to expend funds from proceeds or operations to enhance the functionality and/or value of the system within which the tokens operate?

4. Are purchasers “investing,” that is seeking a return? In that regard, is the instrument marketed and sold to the general public instead of to potential users of the network for a price that reasonably correlates with the market value of the good or service in the network?

5. Does application of the Securities Act protections make sense? Is there a person or entity others are relying on that plays a key role in the profit-making of the enterprise such that disclosure of their activities and plans would be important to investors? Do informational asymmetries exist between the promoters and potential purchasers/investors in the digital asset?

6. Do persons or entities other than the promoter exercise governance rights or meaningful influence?

Interestingly, the 4th factor seems to have little to do with an analysis of third party involvement and instead seems to reflect the Munchee / Gary focus on means of promotion.

Decentralization

Director Hinman allows that the securities analysis of a token may not remain static. He stated:

“If the network on which the token or coin is to function is sufficiently decentralized — where purchasers would no longer reasonably expect a person or group to carry out essential managerial or entrepreneurial efforts — the assets may not represent an investment contract. Moreover, when the efforts of the third party are no longer a key factor for determining the enterprise’s success, material information asymmetries recede. As a network becomes truly decentralized, the ability to identify an issuer or promoter to make the requisite disclosures becomes difficult, and less meaningful.”

Mr. Hinman indicated that Bitcoin clearly met this decentralization criteria and while he had reservations about the “birth” of Ether tokens, he believes that in its current environment Ether meets these criteria.

Mr. Hinman indicated that Bitcoin clearly met this decentralization criteria and while he had reservations about the “birth” of Ether tokens, he believes that in its current environment Ether meets these criteria.

On the one hand, the introduction of the concept of “decentralization” provides a useful framework for analyzing tokens and allows for the possibility that a token launched as a security could lose its reliance on the efforts of others and cease being a security.

However, it seems very likely that this guidance will shift the debate to the definition of the centralization tipping point. For example, if software is launched and the issuer of the tokens that operate the service ceases promotional activities and providing software upgrades, but continues to provide bug fixes, is the network still considered decentralized? Further, if the decentralization criteria are initially met and then use of the network drops, prompting the issuer to resume promotional efforts, can the token return to security status?

Good News/Bad News for SAFTs

In a footnote, Mr. Hinman addressed the SAFT’s — the convertible instrument widely used in the industry for about the last year, although more recently increasingly questioned.

The news here was mixed. Hinman stated:

“…it is clear I believe a token once offered in a security offering can, depending on the circumstances, later be offered in a non-securities transaction. I expect that some, perhaps many, may not.”

The default conversion provision in the initial form of the SAFT was Network Launch — defined as “a bona fide transaction or series of transactions, pursuant to which the Company will sell the Tokens to the general public in a publicized product launch.”

Under Hinman’s analysis, it is entirely possible that conversion will occur before the relevant network is sufficiently “decentralized” and as a result, the tokens on conversion will still be securities. Hinman was clearly uncomfortable making broad statements about SAFTs and encouraged “anyone that has questions on a particular SAFT structure to consult with knowledgeable securities counsel or the staff.”

New Life for Utility Tokens?

Chairman Clayton’s frequent statements that he had never seen an ICO that was not a security, caused many to believe that utility tokens were the Yeti’s of the investment world — believed to exist but never seen. At the end of his remarks, Director Hinman’s statement included criteria that would suggest a token is more of a “consumer item” (which he seems to be using in place of the phrase “utility token”) and not a security. [1]

This discussion was unusual for a couple reasons:

1. It was not expressly linked to the prior discussions about promotion and decentralization. The unanswered question is whether an “and” or an “or” should be applied. In other words, for a token not to be considered a security, does it have to (i) operate on decentralized network and have tokens that operate more like a “consumer item”; or (ii) can it either operate on a decentralized network or have tokens that function more like a “consumer item.” The distinction is critical. If a token meets the criteria of a “consumer item,” does it still need to be deployed on a decentralized network to not be considered a security?

2. The criteria came with the following disclaimer: “This list is meant to prompt thinking by promoters and their counsel, and start the dialogue with the staff — it is not meant to be a list of all necessary factors in a legal analysis.” As a result, there are still many open questions as to what the SEC will treat as “consumer items.”

Conclusion

There was something for everyone in Director Hinman’s remarks, as commentators from diverse perspectives claimed to have found at least partial vindication in the statement. However, after a closer examination of Mr. Hinman’s comments, I was reminded of the reaction to the publication of utility token guidelines in Switzerland by FINMA — which were widely praised for their reasonableness and clarity.

However, a close reading of a translation of those guidelines made it clear that the criteria for a utility token were very narrow and that most tokens would most likely be classified as “hybrid tokens” and therefore would be subject to securities regulation.

It is unclear how many tokens will “avoid” being labeled as securities based on Director Hinman’s guidance. The majority of ICOs I have reviewed anticipate an ongoing role for the issuer long after its network is operational and as a result, would seem to fail the decentralization requirement.

I believe the remarks are most valuable for the window they provide into the SEC’s thinking. Several critical questions, however, remain unanswered:

1. How does one determine that a network has become “decentralized” enough so that the tokens that run on it will not be considered securities? Bitcoin and Ether (today) provide examples of decentralized networks, but left unanswered is whether a somewhat less decentralized network could still run non-security tokens. Further, are there circumstances where a network is deemed to have “centralized” and the tokens then return to being securities?

2. What, if any, role can the issuer have with respect to the secondary market without disturbing the decentralized characterization?

3. The questions raised with respect to “consumer items” above.

Perhaps recognizing the remaining open issues, Director Hinman stated:

“Promoters and other market participants need to understand whether transactions in a particular digital asset involve the sale of a security. We are happy to help promoters and their counsel work through these issues. We stand prepared to provide more formal interpretive or no-action guidance about the proper characterization of a digital asset in a proposed use.”

Finally, I was one of those who found “vindication” in the Director’s remarks. For the last several months, I have been encouraging potential ICO issuers to do an “ordinary” seed / venture raise and delay an ICO for 12–18 months. My logic is based on the following factors:

- The market is very interested in solid blockchain projects and as a result, conventional fundraising is likely to generate attractive valuations.

- Fundraising will be much more modest than the typical ICO and while there is likely to be some dilution, it will be limited (I also do not agree with the view that ICO’s are non-dilutive).

- Fundraising proceeds can be used to fund the building and launching of the network.

- 12–18 months after the initial raise, the network will be functional and the regulatory and accounting environments are likely to be clearer. Both factors are likely to support higher token prices.

Director Hinman made a similar observation: “I believe some industry participants are beginning to realize that, in some circumstances, it might be easier to start a blockchain-based enterprise in a more conventional way.

In other words, conduct the initial funding through a registered or exempt equity or debt offering and, once the network is up and running, distribute or offer blockchain-based tokens or coins to participants who need the functionality the network and the digital assets offer. This allows the tokens or coins to be structured and offered in a way where it is evident that purchasers are not making an investment in the development of the enterprise.”

[1] The criteria were as follows:

1. Is token creation commensurate with meeting the needs of users or, rather, with feeding speculation?

2. Are independent actors setting the price or is the promoter supporting the secondary market for the asset or otherwise influencing trading?

3. Is it clear that the primary motivation for purchasing the digital asset is for personal use or consumption, as compared to investment? Have purchasers made representations as to their consumptive, as opposed to their investment, intent? Are the tokens available in increments that correlate with a consumptive versus investment intent?

4. Are the tokens distributed in ways to meet users’ needs? For example, can the tokens be held or transferred only in amounts that correspond to a purchaser’s expected use? Are there built-in incentives that compel using the tokens promptly on the network, such as having the tokens degrade in value over time, or can the tokens be held for extended periods for investment?

5. Is the asset marketed and distributed to potential users or the general public?

6. Are the assets dispersed across a diverse user base or concentrated in the hands of a few that can exert influence over the application?

7. Is the application fully functioning or in early stages of development?

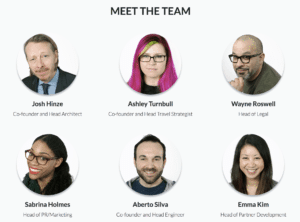

Dror Futter is a partner in the Rimon, PC law firm. Dror’s practice focuses on representing startup companies in their financing and merger and acquisition transactions and their intellectual property, IT and internet agreements. He also advises companies with respect to Initial Coin Offerings and other blockchain legal issues. Dror was the co-founding chair of the PLI VC Law program and hosted their first blockchain legal program. He is a frequent speaker and writer on blockchain legal topics. He is a member of the model forms drafting group of the National Venture Capital Association, the legal advisory board of the Angel Capital Association and the legal working groups of the Wall Street Blockchain Alliance and the Digital Chamber of Commerce. Dror can be reached at dror.futter@rimonlaw.com

Dror Futter is a partner in the Rimon, PC law firm. Dror’s practice focuses on representing startup companies in their financing and merger and acquisition transactions and their intellectual property, IT and internet agreements. He also advises companies with respect to Initial Coin Offerings and other blockchain legal issues. Dror was the co-founding chair of the PLI VC Law program and hosted their first blockchain legal program. He is a frequent speaker and writer on blockchain legal topics. He is a member of the model forms drafting group of the National Venture Capital Association, the legal advisory board of the Angel Capital Association and the legal working groups of the Wall Street Blockchain Alliance and the Digital Chamber of Commerce. Dror can be reached at dror.futter@rimonlaw.com